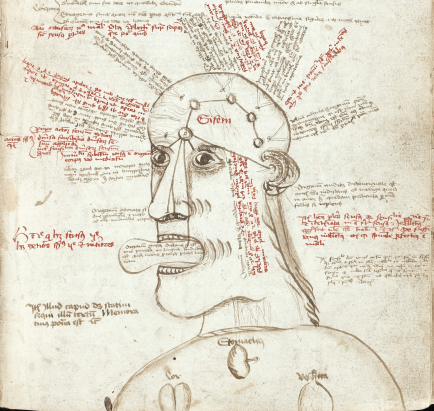

The human sensory and cognitive system, according to the German scholar Johan Lindner of Mönchenburg. Illustration to a manuscript copy of Aristotle’s De Anima (1472-1474), courtesy of the Wellcome Collection (MS 55).

I’ve recently been reading up on medieval theories of cognition. The background is a paper I’m writing on esotericism and “kataphatic practices” – contemplative techniques where the practitioner uses mental imagery, sensory stimuli, and emotions to try and achieve some religious goal: Prayer, piety, divine knowledge, salvation, etc. Kataphatic practices may be distinguished from “apophatic” ones, which, although they may be pursuing the same goals, use very different techniques to achieve them: withdrawing from sensory input and attempting to empty the mind of any content, whether affective, linguistic, or imagery-related (note that the kataphatic-apophatic distinction is more commonly used as synonymous with positive vs. negative theology – that’s a related but separate issue to the one I talk about here). My argument is that esoteric practices are typically oriented toward kataphatic rather than apophatic techniques. The cultivation of mental imagery is usually key – which means that the notion of “imagination” needs to be investigated more thoroughly.

But here’s the thing: The same can be said of mainstream Christianity – and especially in the later Middle Ages and the Renaissance, when currents that scholars usually label “esoteric” started flourishing. Looking at esoteric practices as part of a broader kataphatic stream, then, provides yet another argument for seeing “esotericism” as an integral part of European religious culture.

This line of thought sent me chasing down the rabbit hole of medieval theories of cognition and the monastic reworking of the art of memory, in search of theological and philosophical ideas about the imaginative faculty. It has become increasingly clear to me how much esoteric conceptions of imagination owe, not to Platonism, as the usual story goes, but rather to the thoroughly theologized synthesis of Aristotelianism and Neoplatonism that took shape over several centuries and in several languages, from Avicenna (980–1037) and Averroes (1126–1198) to Albertus Magnus (c. 1200–1280), Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), and – above all others – Bonaventure (1221–1274). Greek and Arabic commentators on Aristotle who tried to make sense of De anima‘s murky passages counted imagination among the “internal senses” connected to the brain, along with “memory,” “cogitation,” and sometimes (e.g. Avicenna) “estimation”. These ideas entered Europe through Al-Andalus (especially in Averroes’ elaboration), forming the foundations of a medieval cognitive science that was rooted in Aristotle, linked to philosophical epistemology and to theological concerns about the relationship between God, the world, and the human soul – at the heart of which was a faculty psychology that gave increasing weight to the faculty of imagination.

The Franciscan theologian and philosopher Bonaventure is the key figure in the story, at least as it relates to the development and spread of kataphatic practices in Latin Europe. This much I have been convinced of by reading Michelle Karnes’ useful book, Imagination, Meditation, and Cognition in the Middle Ages (Chicago UP, 2011). By putting Aristotle’s De anima in an Augustinian Neoplatonic and illuminationist framework, the Seraphic Doctor developed a fully-fledged “cognitive theology” – fully set forth in his Itinerarum mentis ad Deum (“The journey of the mind to God”). Following Augustine (in the final part of De Trinitate), Bonaventure saw the faculties of the human mind as a sort of mirror of the Trinity. But unlike Augustine, Bonaventure’s Aristotelianism led to a special interest in the imagination, and especially in how it is able to mediate between fallible sense impressions and true apprehension by the “agent intellect” (which, at least since Avicenna’s interpretation, had been associated directly with God rather than with individual human faculties).

Taking another cue from Augustine, this time from his illuminationist epistemology, Bonaventure came to associate the imagination’s ability to abstract things that are true from the impressions of the material senses with Christ. Due to the Incarnation, Christ himself is the perfect mediator – and Bonaventure sees the cognitive process from material sensation to divine apprehension as analogous to the movement from Christ’s humanity to his divinity. The imagination is itself an image of Christ’s incarnation, and Christ, through his incarnation, is the super-image that guarantees safe passage from matter to spirit (or from sensation to knowledge). Thus, Christ intervenes directly every time a human extract true abstractions (or “species”, to use the scholastic term – see Robert Pasnau’s Theories of Cognition in the Later Middle Ages for a particularly clear discussion) from mental images, grasping some of the truth originally put into the world by God. In a sense, Christ incarnates in the imagination.

Karnes summarises Bonaventure’s view nicely:

“the mind, when it knows anything, journeys from Christ’s humanity to his divinity. Shining the divine light of illumination on imagination’s phantasms, Christ manages the transition from sensory to intellectual cognition. Understanding thus conceived is a journey through Christ, one that begins with this world and ends with God.” (Karnes, Imagination, 111).

The practical upshot of this cognitive theology (of which there are many other facets – I’ll not even mention the role of the Holy Spirit…) is that contemplation on the mind’s own cognitive processes – how we move from sense impressions to mental images, how images are formed from various sources and relate in various ways to truth and untruth, and how we come to understanding through “illumination” – constitutes a way to knowledge of God, and more specifically of the Trinity (as Augustine already held).

But what if the imagination – already associated with Christ – is put to the task of forming images of Christ? Would that not be the most powerful and intimate way to access divine things through one’s mind (or internal senses)? It’s the armchair mystic’s wet dream. Karnes argues, in my view convincingly, that this was the logic underpinning Bonaventure’s later work with producing gospel meditations – instructions intended for a broader audience on how to imagine, contemplate, and feel with Christ – especially focusing on the passion.

Karnes shows how Bonaventure’s gospel meditations (i.e., Lignum vitae [1260], the Vitis mystica [c. 1263], and De perfectione vitae ad sorores [1259-1260]) in fact tend to follow the same structure, from senses to mental images to illumination and knowledge of higher things, that his cognitive theology had already outlined – creating a direct link between his theoretical and his practical work. By doing this, he also contributed to what was becoming a big trend transforming Christian religious practice: the massive spread of practices aimed at personal piety through prayer and the contemplation of images. Devotional literature, such as the pseudo-Bonaventurean Meditationes vitae Christi (early-fourteenth century) and the Stimulus amoris (James of Milan, original late-thirteenth century but massively expanded upon in manuscript copies for centuries), were among the most popular manuscripts of the later middle ages, if we are to judge by the sheer numbers of surviving manuscripts. In various versions and stages of completion the latter work alone exists in as many as 374 known manuscripts (see overview in Karnes, p. 146).

Climbing out of the rabbit hole, what this means is that by the late thirteenth century and certainly by the fourteenth, there was a lot of kataphatic practice going around in Christian piety. The cultivation of the imaginative faculty was at the core of a mainstream religious practice, undergirded by a robust (for the time) philosophy and theory of the mind. Forms of contemplation that had traditionally been associated with monasticism were seeping out into the laity. This may help explain why we also see such a creative flowering of “heteropraxy” related to cultivation of imagination during the same period. I am thinking especially of the ars notoria and innovations on it, like John the Monk’s Liber florum (check out Claire Fanger’s Rewriting Magic for a wonderful recent close-reading of this text), but moving forward a century or two, it is also tempting to look at links with the rise of theosophical Pietism in Protestant lands – from Böhme to John Pordage and Jane Lead. One could be forgiven for thinking that the imagination-fuelled kataphatic meditations that Bonaventure helped popularize in the thirteenth century created sparks which, in time (and not least with the upheavals of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation), lit that wildfire of “enthusiasm” that guardians of religious orthodoxy complained so much about by the seventeenth century.

But also on the theoretical side, it is tempting to say that the scholastic imagination exerted a major, long-lasting influence on various “esoteric epistemologies”. In a sense, this is a trivial observation: the imagination as a separate cognitive faculty, or an “inner sense” involved with perception and apprehension is an Aristotelian notion, and that Aristotelian notion re-entered European intellectual discourse through the Persian, Andalusian, Italian, and German scholars I have mentioned here. Moreover, that the “phantasms” created by the imaginative faculty can be mined for mystical insights is a notion that appears to enter European religious/intellectual discourse through Bonaventure’s synthesis of Aristotelianism and illuminationism.

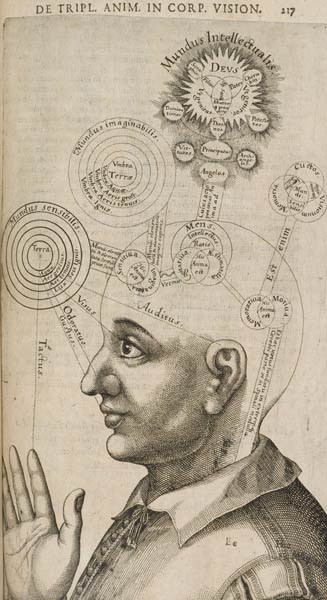

So, if we look at the famous illustration in Robert Fludd’s Utriusque cosmi historia (“History of the two worlds”, 1617-1621) of how the cognitive system and (external and internal) senses reach out to the three worlds, at least on the cognitive side we still see the basic framework of Avicenna, Averroes, and Bonaventure. He lodges “imagination” between “sensation” and “mind”, with a window on to the mundus imaginalis, the “shadows” of the world. The connection of God and the angels with the “intellectual world”, influencing the “mind” and playing a direct part in assessing the images sent forward from imagination, still echoes the scholastic interpretation of Aristotle’s “agent intellect” acting on the “passive intellect”. (update: Phil Legard has a nice discussion of Fludd’s cognitive theory over at Larkfall).

Considered as a true longue durée, we could follow the influence of the scholastic imagination even further, into the Theosophical, “Hermetic”, New Thought, and New Age conceptions of modern occultism and contemporary esotericism. Going down the rabbit hole of medieval cognitive science, then, may lead us to balance the traditional assumptions about esotericism as primarily connected with a revival of Neoplatonism. This may be true in the philosophical, cosmological, and theological senses. But when we consider the nitty-gritty of how one faculty – the imagination – came sailing up as a possible, yet unruly instrument for attaining knowledge, inspiring a host of practices for cultivating mental imagery, we find a good portion of medieval Aristotelianism as well.

This blog post by Egil Asprem was first published on Heterodoxology. It is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Excellent post, would enjoy looking at anyone whose Trinitarian visions have been interfaith and emerged similarly out of intensive prayer or meditation.

Thank you for sharing this very interesting research, drawing attention to the significant engagement of the sensual and symbolic stimuli, both in esoteric and more mainstream Christian practice. It raises many fascinating questions, and I look forward to reading more.

Thank you Susan. I am working on two article manuscripts related to this topic at the moment, and will post any updates on that here.

Many thanks

[…] one of the most exciting developments in Western Esoteric studies of late. Thanks also to Egil for linking here on his blog! In fact, speaking of Egil’s work, there is definite overlap with my own experiential work […]

[…] suffice to say this is the explanatory counterpart to my recent Correspondences article on the “Scholastic imagination”). Markússon’s article (“Indices in the Dark: Towards a Cognitive Semiotics of Western […]