In the previous post on Rupert Sheldrake’s Science Delusion, I noted that the overall argument is based on a number of misrepresentations and stereotypes of what “science” is up to. The reader gets the impression of a monolithic structure, big-S-“Science”, now dominated by Ten Dogmas, like commandments cut in stone tablets. The history of science has, of course, been rather more complicated. Several of the dogmas do not even correspond well with the actual theories that are pursued today: at best they represent a pointed caricature, at worst, they build on stereotypes crafted about a century or longer ago, that hardly have any relevance for contemporary scientific practice. Even to the extent that some of the “dogmas” refer to presently widespread theoretical or methodological conventions, holding these to be fixed dogmas obscures the fact that they are the outcome of long and sometimes complicated historical developments, both internal and external to science. In short: that x is a widely held belief does not make x a “dogma”; that y is a commonly recommended way of pursuing a task does not make y a dogmatic procedure.

As promised in the previous post, I will go through the ten dogmas one by one to demonstrate some of these points. In the present one we shall focus on the first two, which have to do with questions about mechanism, vitalism, scientific method, materialism, and the problems of defining “consciousness”. We will visit some historical backgrounds and parallels to Sheldrake’s criticism of science, and test his claim that science has closed certain questions “dogmatically”, by holding them up against the actual historical developments of some of the special sciences. Without further ado, here goes dogma #1:

1. “Everything is mechanical”.

The first scientific commandment appropriately holds that “Thou shalt have no other theoretical framework than the mechanical”. According to Sheldrake, “modern science” = “mechanical theories”. That science “reduces everything to mechanical processes”, essentially to “matter in motion”, is one of the older and most fundamental accusations on the list. It can be traced all the way back to the birth and spread of the so-called mechanical philosophy of nature itself in the early modern period. According to the charges,”the mechanistic dogma” holds that all phenomena are straight-jacketed into “mechanistic” and “materialist” frameworks.

Complaints about this are often made with reference to the phenomena of life and minds. As Sheldrake writes in the introduction to his book: “Dogs are complex machines [according to science], rather than organisms with goals of their own” (p. 7). Maybe so, but statements such as these rest on a false dichotomy: isn’t the marvel of the modern life sciences precisely that they have been so surprisingly successful in accounting for complex organisms in mechanistic terms? No mysterious vital powers needed? Castigating biological science for not having produced anything else than mechanistic explanations, when those in fact have been staggeringly successful, amounts to little but a case of petitio principii.

The portrayal of “mechanism” in such criticisms (and I’m not only thinking of Sheldrake here) is really not very sharp, especially from a philosophical point of view. First of all, it might be a good idea to differentiate between philosophical (or metaphysical) mechanism and explanatory mechanism. One claims the world really is a giant mechanical machine, and therefore ultimately allowing to be explained that way; the other is more modest, emphasising that, as an explanatory practice, one ought to look for concrete mechanisms and physical interactions. At any rate it would be more accurate to describe “mechanism” (both philosophical and explanatory) as holding that all phenomena of nature can in principle be explained in terms of mechanistic interactions. The term “in principle” is absolutely crucial: pointing to the lack of a mechanistic explanation of phenomenon x is not enough to dispel mechanism as such. Instead, mechanism is a powerful heuristic for seeking robust explanations of new phenomena.

In other words, the first dogma is not very well stated. But even more importantly: if we read Sheldrake charitably, and presuppose 1) that he really means to charge science with being “mechanistic” in a more complex and nuanced way (let’s call it “sophisticated mechanism”, and 2) that science, by and large, actually does cling to such a sophisticated mechanism, is it really correct to call the stance a dogmatic one?

Historically speaking, the mechanism/non-mechanism debate is very much a science-internal dispute, and it has been an open and lively one. To the extent that it now is now a settled debate, in which there exists a general consensus, it has been settled by science-internal procedures (what are the best arguments? how can we best account for the totality of what we know? what research practice seems to yield the best results?) rather than by decree.

The anti-mechanical stance is thus by no means new in the history of science, and Sheldrake joins a long tradition of other biologists when he raises the issue based on a conceived problem to account for living organisms. Traditionally, the conflict has been between mechanism and teleology in various forms, and in more recent history, between mechanism and various positions going under terms such as organicism, holism, or emergentism.

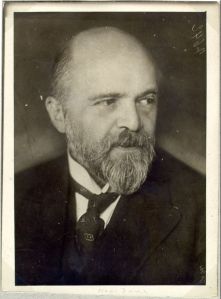

One historical example is the neo-vitalism controversy arising from scientific concerns in late 19th and early 20th century embryology. The problem of giving satisfactory mechanical explanations of central features of organic life, such as heredity and embryonic development, was the source of this dispute, which concerned not only the philosophical “superstructure” of the life sciences, but practical methodological issues as well. In the 1890s, the German embryologist Hans Driesch’s experiments with sea urchin eggs seemed to suggest that each individual cell after the first cleavage could potentially develop into a whole organism. This contradicted the best mechanistic theory available at the time, namely August Weismann and Wilhelm Roux’ theory that all the hereditary material was present in the fertilized egg and then distributed through cell division. After trying in vain to make his findings square with a mechanistic conception, Driesch proposed a radically different theory. In his 1899 monograph Die Lokalisation morphogenetischer Vorgänge; ein Beweis Vitalistischen Geschehens Driesch proposed that organisms were “harmonious equipotential systems”. The neo-vitalistic concept of entelechy was born: a non-material directing principle that already contained the plan of the whole organism within it, directing the production of biological forms by way of a mysterious non-material, teleological agency .

It was a concept not unlike Sheldrake’s own “morphic resonance”. While Die Lokalisation morphogenetischer Vorgänge was a rather less sexy title than Sheldrake’s A New Science of Life, the biographical similarities of the authors are rather similar as well. Both were young biologists with impressive early achievements, whose first major publication would be on a vitalistic theory at odds with most of their peers.

Another similarity concerns the two scientists’ attitude to criticism. Driesch frankly did not spend much time listening to his critics – even when better mechanistic theories were developed in his field, solving the problems he had been struggling with and achieving great successes, he continued talking about entelechy. While embryologists were busy discovering the role of chromosomes in heredity and laying the groundwork of the modern synthesis of Mendelism, Darwinism, and population statistics, Driesch in fact expanded the principle of entelechy, to deal with contexts quite different from the original embryological one. Again, not unlike Sheldrake, Driesch took his biological concept to bear on subjects such as parapsychology, the soul, and the philosophy of life. Both Sheldrake and Driesch are good examples of what I call “discovery enthusiasm”: scientists who think they have made a revolutionary break-through, follow up by expanding the application of their discovery to increasingly more lofty fields, and typically meet resistance and counter-theories by increasing their zeal and looking for support in popular, philosophical, or religious communities rather than in their original scientific community.

While the vitalistic controversy started by Driesch was, from a scientific point of view, settled within few years, the door to vitalism and other non-mechanistic theories of life remained temporarily open in the scientific discourse of the early 1900s. On the more philosophical and speculative side, we have the crazed popularity of Henri Bergson’s vitalistic philosophy, the creation of various philosophies of emergence (notably by philosopher Samuel Alexander, the biologist/psychologist C. Lloyd Morgan, and philosopher C. D. Broad), and the “process philosophy” of Alfred North Whitehead. In addition to these, a significant number of celebrated biologists adopted broadly “organicist” rather than “mechanistic” research methods in the period between 1900 and 1940. Hans Spemann was even awarded a Nobel prize of physiology in 1934 for his work in the 1920s (with the PhD student Hilde Proescholdt – a poor victim of the “Matthew effect”, but that’s another story) on his essentially organicist concept of “the organizer”. When the scales tipped again, it was not so much a result of a repressive scientific establishment forcing its way, as the heavy weight of successful mechanistic explanations across a wide spectrum of biological and biochemical research that had been technically impossible in the 1920s.

Finally, we should note that being an organicist and hence limiting the scope of “mechanism”, does not necessarily mean a hostility towards metaphysical views such as “materialism” or physicalism. This can be illustrated by other famous biologists with organicist leanings in the early 20th century, such as Joseph Needham. Needham was drawn to non-mechanistic theories of life from Friedrich Engels’ decidedly materialist philosophy of science. In fact, one way to distinguish “vitalism” from “organicism” is that vitalists are committed to non-materialism, while organicists can easily remain materialists. Under this definition, Sheldrake in fact appears more like a full-blown vitalist than an organicist.

This becomes clear in that he considers the second dogma of science to be:

2. Matter is unconscious.

I will not spend too much time on this particular “dogma”, but rather treat it in continuation with the above. “Consciousness” is a common preoccupation of vitalists, who typically connect the conscious to the mysterious life force, and need both of which to be somehow irreducible and essential forces in the world. This means a break away from materialism and physicalism: whatever consciousness is, it is something other than a mechanical effect of material substances. Thus one might be drawn to various “animistic” theories, where” souls”, “spirits”, or other forms of conscious agents, are separable from material bodies and only inhabit them. That would be a rather common (and some would say intuitive) form of dualism. Alternatively one might want to save a monistic worldview, and hence avoid problems with mind/body dualism by postulating a form of panpsychism. Perhaps everything is inherently conscious, inherently “alive”?

There have been many proponents of various versions of this view throughout the history of western philosophy, but Sheldrake is probably quite right in stating that it is never considered seriously by science today. To cite his description of the “second dogma”:

“All matter is unconscious. It has no inner life or subjectivity or point of view. Even human consciousness is an illusion produced by the material activities of the brain.”

These are extremely tough questions, and it simply will not do to castigate science for not considering that “matter” might be “conscious”. (What is that even supposed to mean?) Even within the science that deals most closely with the field from which we happen to know about such a thing as “consciousness” (or think we do, anyway – let’s not be dogmatic about this!) – psychology – the concept has always been notoriously vague, imprecise, and void of explanatory power. When psychology was getting properly professionalised around the beginning of the 20th century, the concept was about to be ditched completely. Not only by the behaviourists – the movement pioneered by John B. Watson in 1913, but by functionalists as well. Anyone who has bothered to read Watson’s paper, “Psychology as the Behaviorist Views It” (which I believe has gotten unnecessary bad reputation following Noam Chomsky’s dismissal of Skinner’s behaviourism and the foundation of cognitive science), will have found that the main objection there is not to a metaphysical theory, but to problems of precision in terminology, methods of measurement, experimental conduct, and theory building. Getting away from a focus on introspective analysis of the “contents of one’s mind” or “the structure of consciousness”, was necessary in order to build a psychological science that could say anything meaningful at all about the workings of minds.

Since then, of course, psychology has gotten much more sophisticated. Cognitive science has put mental content and internal processes on the map again, enhanced by an advancing neuroscience. But the point still remains: if determining conscious activity in animal and even human subjects has proved so incredibly difficult, how much sense does it make for a scientist to ask whether or not a grain of sand is “conscious”? What would be the criteria by which one could determine such a question? And more importantly, what would be the sufficient criteria to conclude that the speck is, indeed, unconscious?

A science that would treat random objects as conscious without considering questions such as these would be a truly dogmatic science. But the epistemological problem runs even deeper: To insist on keeping the question open even when there are scientific criteria around (in this case those of psychology and the philosophy of mind) that, if they were employed, would yield pretty clear answers, amounts to a form of special pleading. Or else a serious case of the (incredibly common) fallacy known as equivocation: if a pebble on the beach is conscious, it is not conscious in the same sense, or by the same definitions, as we intend when talking about human subjects as being conscious. The science of consciousness has descended into a game of words.

So much for mechanism, vitalism, panpsychism and consciousness. Next up we look at questions such as: Are the laws of nature fixed? Does nature have a purpose? And more importantly: is science dogmatic about these issues?

![]()

This work by Egil Asprem was first published on Heterodoxology. It is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

“To insist on keeping the question _open_ even when there are scientific criteria around (in this case those of psychology and the philosophy of mind) that, if they were employed, would yield pretty clear answers, amounts to a form of special pleading.”

How could anyone insist on keeping that question open when there are methods that _might_, if they were employed, prove your point of view? 😉

I see a tendency that more ignorance and uncertainty in certain fields is claimed than there really is room for. And once ignorance has been claimed (ie., “science has no clue xyz…”), the road is open to present all sorts of things as valid suggestions (i.e. “…so therefore abc might just as well be the case”). The problem is that by fabricating doubt, one clouds the fact that the alternatives abc might in fact be in conflict with lots of solid knowledge, and hence much more controversial than what appears on the surface, when presented in a theoretical vacuum.

The problem is that you are invoking “promissory materialism”: the notion that although materialistic science (if you’ll allow the term for the purposes of this discussion) hasn’t yet discovered the answer (in this case to the “hard problem” of consciousness), nevertheless it will do so, given time and resources. This sort of argument is covered extensively by Thomas Kuhn as a reaction to (anomalistic) phenomena which don’t fit the current paradigm. It is not a scientific argument, since not based on empirical evidence, but is rather an appeal (indeed a “special plea”) for research to be conducted only in the manner of which one approves.

Sheldrake, at this point, would most likely also point to the case of genetics as an example of an area of materialistic science that has so far not been able to show how organisms develop from embryo to adult (in terms of form, rather than mere protein production). It has been promised for many decades that genetics will provide the answer and that consequently we don’t need to examine “morphogenetic fields”, and it is still being promised — see for example the “Genome Wager”: http://www.sheldrake.org/D&C/controversies/genomewager.html

The key point I’m making is that consciousness research is not an area of “normal science” (in the Kuhnian sense), and there is no guarantee that research will actually progress if based only on the prevailing paradigm. Further, I put it to you that by arguing that materialism is the correct consensus view and that to posit alternate theories requires “special pleading”, you are in effect proving Sheldrake’s point that “matter is unconscious” has become a “dogma”.

Thanks for a good and well-stated counterargument. I don’t think it really responds to what I meant with the accusation of special pleading however. My point was that, in order to insist that whether or not “matter” is somehow “conscious” is a completely *open question*, one must implicitly, but effectively, ignore entire fields of inquiry (e.g. neurobiology, cognitive science, and associated philosophy of mind), and the definitions, theories, and explanatory schemes that overall work very well in those compartments. In this sense it becomes a case of special pleading – the question is taken to be more “open” than it really is, and suggested _answers_ less controversial and problematic than they really are.

As to the other examples of anomalies, this is also an area where I think Sheldrake is getting carried away by reading Kuhn. To fault a normal science for not (yet) having final answers on a certain subject is not very convincing in my view. Even less convincing, though, is to postulate a fancy new concept to grasp this anomaly, and call it a revolution. To stay with Kuhnian concepts, it is easy to mistake mere ad hoc thinking for a genuine “paradigm shift”. For what new have we really learned about the evolution of conscious human beings from the primordial soup by postulating that “matter is conscious”?

The trouble is that you want to have your cake and eat it. On the one hand, you say that mainstream science is clearly heading in the right direction (even if it hasn’t got there yet), so Sheldrake’s line of inquiry is, by consensus, perverse. On the other hand, you deny Sheldrake’s claim that that “most scientists” have imposed a kind of dogma against Sheldrake’s line of inquiry — that this is somehow a misunderstanding.

I frankly fail to see how you can reconcile these contradictory positions without resorting to value judgments about the current scientific “state of play”; which judgments must inevitably be based on your own particular knowledge of the fields in question; i.e., your opinion. Indeed this is the general position you have taken.

Turning, then, to the OED definition of “dogma”, I find:

1. That which is held as an opinion; a belief, principle, tenet; esp. a tenet or doctrine authoritatively laid down by a particular church, sect, or school of thought; sometimes, depreciatingly, an imperious or arrogant declaration of opinion.

2. The body of opinion formulated or authoritatively stated; systematized belief; tenets or principles collectively; doctrinal system.

I’ll let this point rest here, but before letting you get on with the next instalment of your review I just wanted briefly to touch upon your comment about Kuhn and whether formative causation / morphic resonance is an “ad hoc” theory. My edition of Kuhn doesn’t have an index, but anyway I think you might be referring to Popper, who says:

“Whenever the ‘classical’ system of the day is threatened by the results of new experiments which might be interpreted as falsifications according to my [sic] point of view, the system will appear unshaken to the conventionalist. He will explain away the inconsistencies which may have arisen; perhaps by blaming our inadequate mastery of the system. Or he will eliminate them by suggesting _ad hoc_ the adoption of certain auxiliary hypotheses, or perhaps of certain corrections to our measuring instruments.”

On this basis I can’t agree at all that formative causation is “ad hoc”. In fact formative causation is not limited in scope in the manner implied by Popper, rather it is universal in scope and claims predictive power in all sorts of areas, not merely in the field where the original observations were made (biological development). It is certainly not an adjunct to some other theory, designed to cover up anomalies, but has surprising implications that do away with a number of unnecessary assumptions (e.g., that nature’s laws are fixed) by showing them as a special case of a deeper principle. Thus, if true, it would be revolutionary. However, since you’ve raised the subject of ad hoc theories and the philosophy of mind, I might cite “eliminative materialism” as a theory which does seek to “eliminate” those “inconsistencies which may have arisen” in respect of the apparent existence of consciousness, by denying such anomalies exist!

Eliminative materialism and similar positions (e.g. epiphenomenalism) are indeed more consistent philosophies of mind in the sense that they deny the problem, and for all their absurdity (in the sense of breaking with ingrained intuitions) I don’t think they can or should be ruled out. In fact this is another possible line of critique against the way Sheldrake handles these philsophical questions: when it comes to positions that would force us to radically rethink our conceptions of free will, intentionality, and consciousness itself, he often finds it enough to insinuate that these are absurd because in contradiction with those ingrained intuitions. This of course is not something particularly Sheldrakian – lots of philosophers do it all the time. Personally, however, I think intuition (and now I mean in the more technical philosophical sense) is overrated, and that a crucial endevour of science and philosophy is precisely to challenge them.

As for the point at the beginning of your comment, I wanted to make clear that I don’t see a paradox here. What I am saying is that the charge of dogmatism (with all its rhetorical connotations, many of which are not in your OED definition) fails, because it 1) ignores the long and complex history of discovery and justification that underlie the apparent “closure” of any specific question, and which are naturally and legitimately reactivated whenever the questions are asked over again; 2) that it confuses the call for explanatory coherence with a “dogmatic closed-mindedness”. Curiously, so-called coherence theories are part of the same post-positivist legacy in the philosophy of science that Sheldrakes beloved Kuhn belongs to (but it is stated much more precisely by people like Quine and Davidson). I might get back to this in later installments.

Re: “intuition”, Sheldrake does sometimes refer to popular belief and intuition as being a starting point for experimentation (e.g., the telephone telepathy & “Dogs That Know…” experiments), usually in the context of questioning why certain intuitions (those which don’t fit into the materialist paradigm) are routinely ignored or dismissed without examination. He has also called for public funding of science to be partly (1%) on the basis of what people are interested in — in which scenario his research would obviously benefit.

As for the “long and complex history of discovery and justification leading to the apparent ‘closure'” of any given questions like the ones posed by Sheldrake, that would rather depend on actually making a scientific case that Sheldrake’s comments and hypotheses ought to be regarded as “fringe” on the basis of empirical evidence (rather than metaphysics or the history of attitudes amongst scientists), though I appreciate your review has a different focus. I would, however, point out (w.r.t. to the article I linked-to on Facebook) that his scientist opponents apparently don’t feel the need to do so. And as regards “explanatory coherence”, Sheldrake’s “morphogenesis” is arguably synonymous with “soul”, which seems pretty coherent. Again, I feel you would have to make the alternate case if you wish to argue that formative causation is either “ad hoc” or incoherent, but perhaps we could continue this discussion following the next instalment of your review. It might be more fun if you’re interested in getting into the experimental evidence — I find some of this philosophy of science a little dry! 🙂

Dry but important. 🙂 Otherwise there is no direction, only a collection of impressions, information and opinion. Hopefully I’ll get around to the next post soon.

[…] the previous post on Sheldrake’s Science Delusion I discussed the first two dogma, concerning the “mechanical philosophy” and its […]

[…] old ones who need to refresh their memories, previous installations in the series are found here, here, and here. Without further ado, let me get started on an evaluation of the fourth dogma ascribed to […]